Biomes course

-

Posted On Biomes course

Posted On Biomes courseBiomes, a full course for beginners to biomes

A full course for beginners to biomes, covering in detail every biome of earth according to the LONS08 specification. Includes the full video for each…

-

Posted On Biomes course

Posted On Biomes courseBiomes, introduction, the living landscapes of earth (0)

When you look at pictures of the Earth from space, what’s the first thing that you see? A blue marble, as some have described it.…

-

Posted On Biomes course

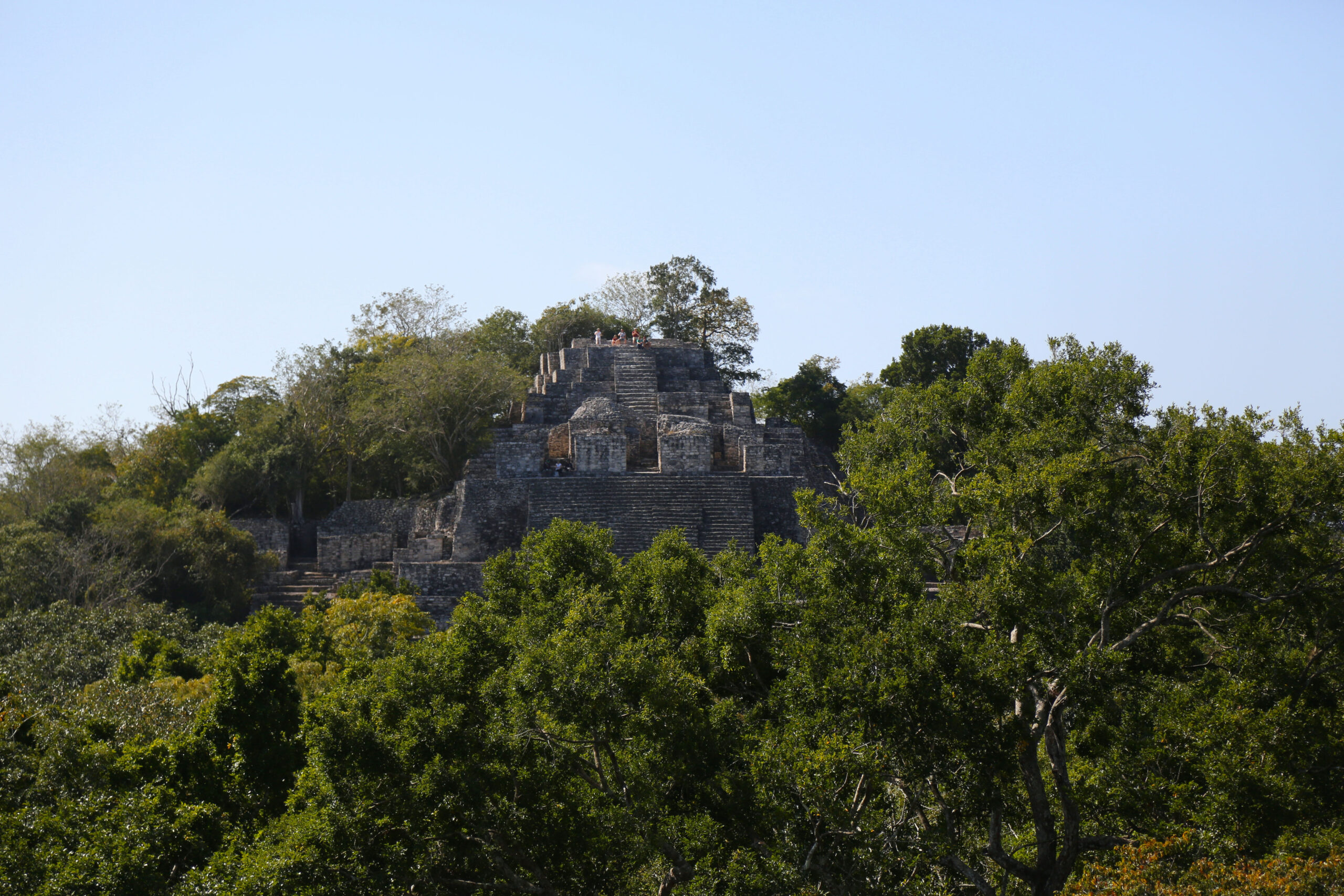

Posted On Biomes courseTropical forests (1)

EVERGREEN & SEASONA. It is fitting that we begin our journey across the biomes of Earth with the one that we perhaps hold the most…

-

Posted On Biomes course

Posted On Biomes courseSavannah (2)

THE MIXED GRASS AND WOODLAND OF THE TROPICS. The vast open country of the tropics. A patchwork of trees and shrubs on a bed of…

-

Posted On Biomes course

Posted On Biomes courseShrublands (3)

SUBTROPICAL & MEDITERRANEAN SCRUB Often overlooked, these relatively arid regions of earth take second or third place to forests or grasslands when it comes to…

-

Posted On Biomes course

Posted On Biomes courseDeserts (4)

THE BONES OF THE EARTH EXPOSED This is what the bare earth looks like, the bones of our planet revealed as the skin of vegetation…

-

Posted On Biomes course

Posted On Biomes courseGrasslands (5)

STEPPE, PRAIRIE, MEADOW, PAMPAS & VELDT Grass. If there is one plant that has come to dominate our world, it’s this. Occupying every biome on…

-

Posted On Biomes course

Posted On Biomes courseTemperate forests (6)

THE BROADLEAF & CONIFEROUS WOODLANDS OF THE MID-LATITUDES The temperate regions of our planet were once covered in forest, an endless swathe of trees of…

-

Posted On Biomes course

Posted On Biomes courseThe Taiga Biome (7)

THE BOREAL FORESTS A sea of the darkest green, stretching unbroken from coast to coast. The continental north is dominated by this, the last great…

-

Posted On Biomes course

Posted On Biomes coursePolar biomes (8)

At the ends of the world, the sun’s reach is weak. Life struggles or is entirely absent. And indeed what life could survive in a…