Stephen

-

Posted On Climate course

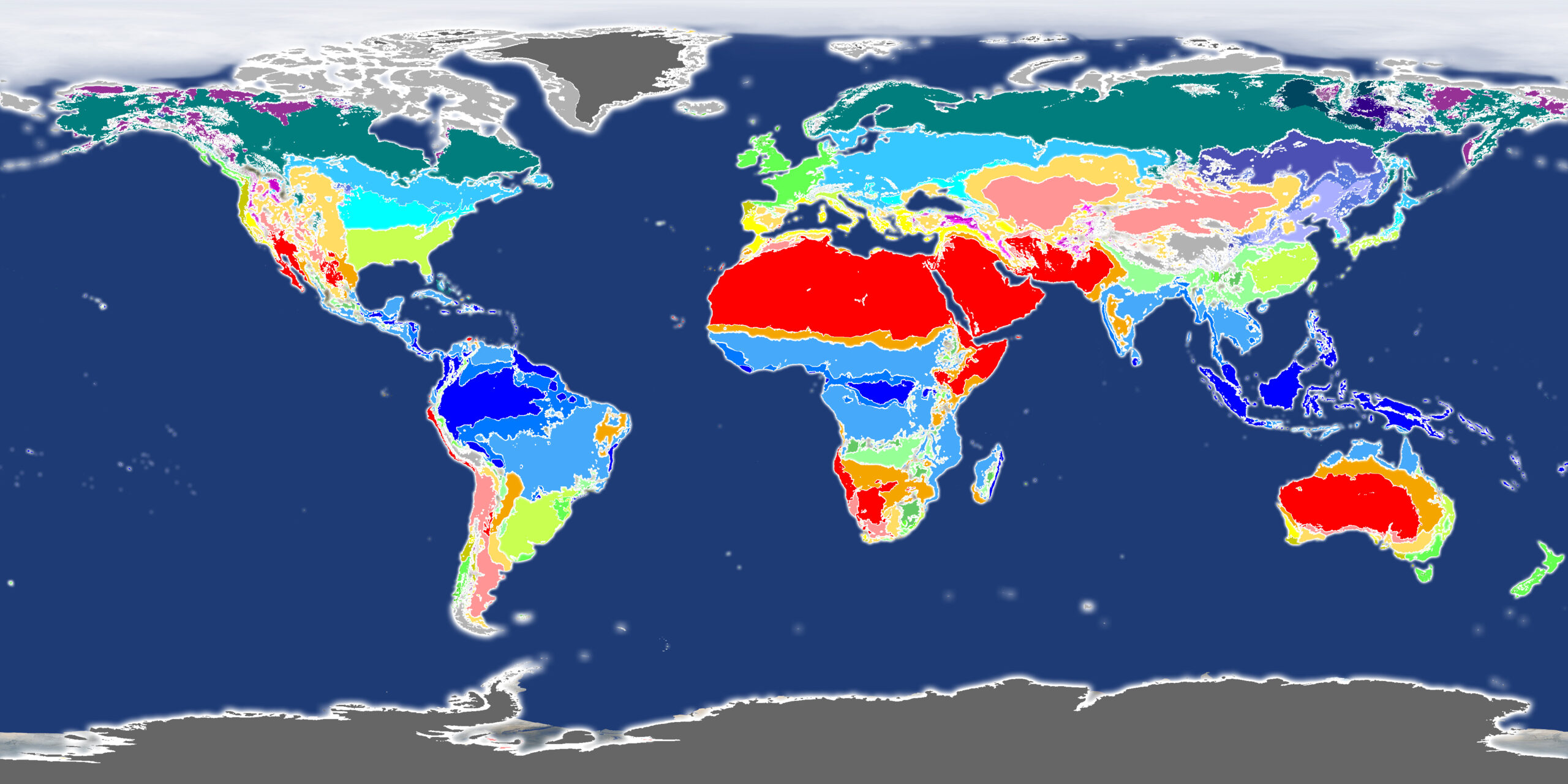

Posted On Climate courseIntroduction (0)

Planet Earth. Our home. Among all the worlds in the universe, it’s the only one we know that harbours life. A spinning globe of blue,…

-

Posted On Climate course

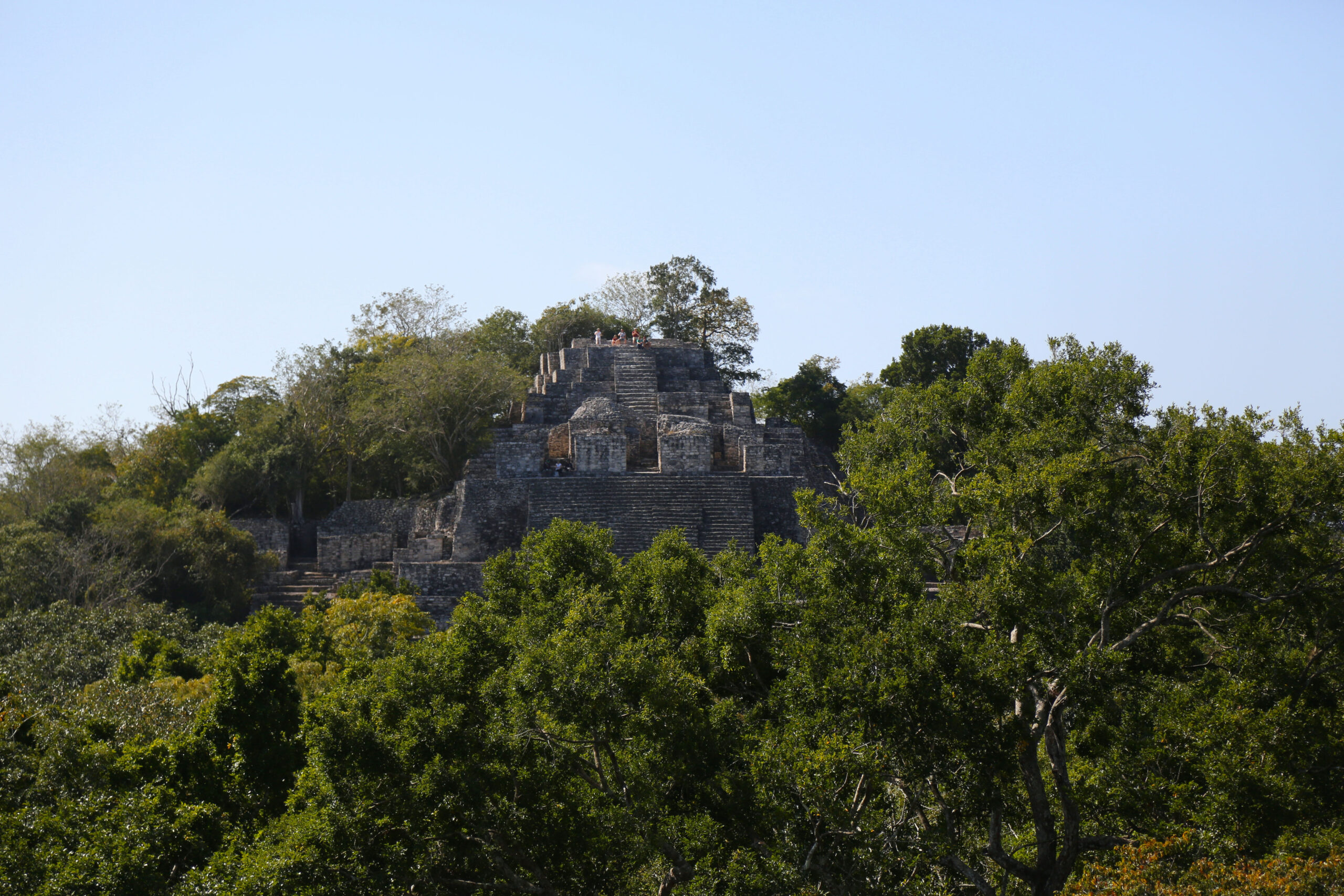

Posted On Climate courseTropical Rainforest (1)

Imagine a place with no seasons. Where every day seems like the last. A place where it rains almost every day. A place of constant…

-

Posted On Climate course

Posted On Climate courseTropical monsoon and tropical savannah (2)

For so many of us in the developed world, the seasons are defined by temperature. The freshness of spring, the heat of summer, the chill…

-

Posted On Climate course

Posted On Climate courseSubtropical Highlands (3)

There are places on this planet, where altitude and latitude combine to form a harmonious, temperate balance. High in the clouds of the tropics, there…

-

Posted On Climate course

Posted On Climate courseHot Deserts (4)

Water. Without it, life cannot exist. The places on our Earth denied it, are empty, barren places. And yet even these have a stark, almost…

-

Posted On Climate course

Posted On Climate courseHumid Subtropical (5)

Hot summers, cool winters, and plenty of rain. You could live in a place like this, right? Well millions would agree with you. Because out…

-

Posted On Climate course

Posted On Climate courseMediterranean (6)

The world’s most famous sea. Endless coastlines and beaches. Histories and culture as rich as any on earth. Blessed with one of our planet’s finest…

-

Posted On Climate course

Posted On Climate courseOceanic (7)

Cool oceans. Westerly winds. Storm-driven rains. Half-way between equator and pole, the lands on the westerly fringes of the continents are dominated by their neighbouring…

-

Posted On Climate course

Posted On Climate courseCool deserts (8)

Majestic landscapes. Endless plains. Where a lack of rain combines with cold winters. On the wrong side of mountains, or thousands of miles from the…

-

Posted On Climate course

Posted On Climate courseContinental (9)

The great plains of the northern continents. Lands of hot summers, but cold winters. The bread baskets of the developed world, they are also home…