Hot Deserts (4)

Atmospheric Origins of Hot Desert Climates

As we transition away from the equator and move toward the poles, we pass through one of Earth’s most extreme climate zones: the hot deserts. But why do these dry, sun-scorched bands exist at all?

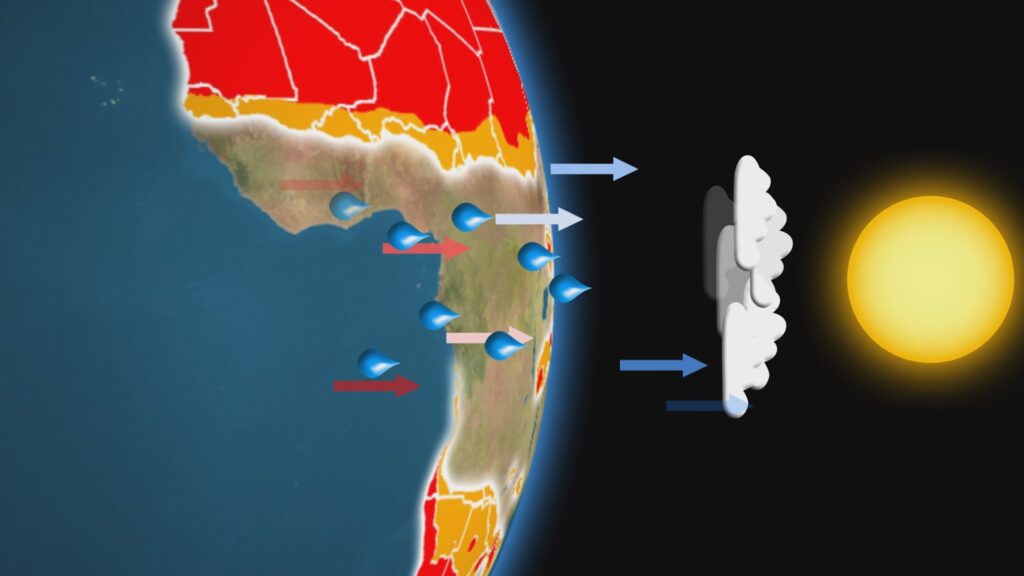

The answer lies in the atmospheric circulation patterns that govern global climate. Near the equator, the Sun’s energy heats moist air, causing it to rise rapidly into the upper atmosphere. As this air ascends, it cools, and its moisture condenses, falling as heavy rainfall. This process is what fuels the tropical rainforests.

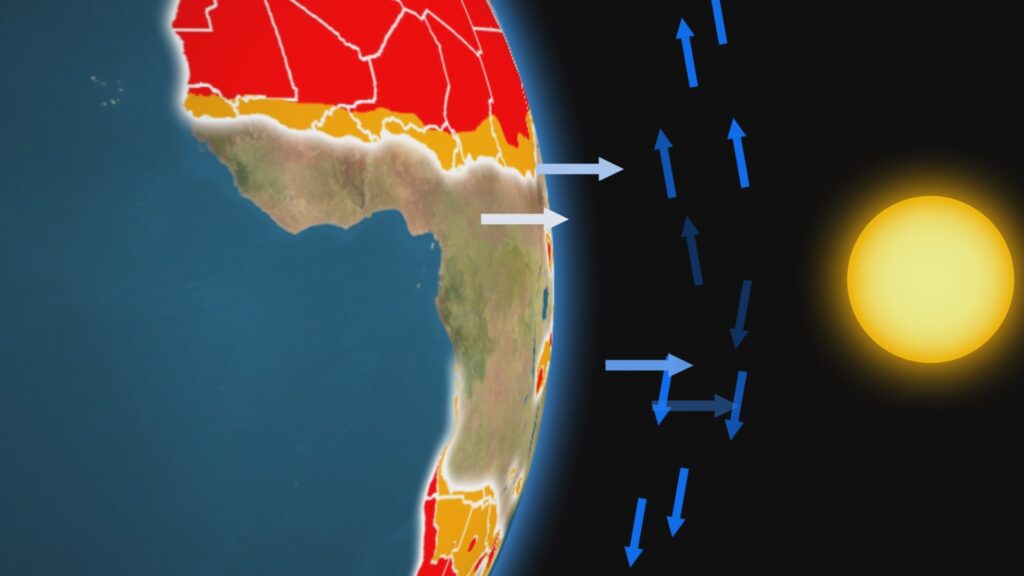

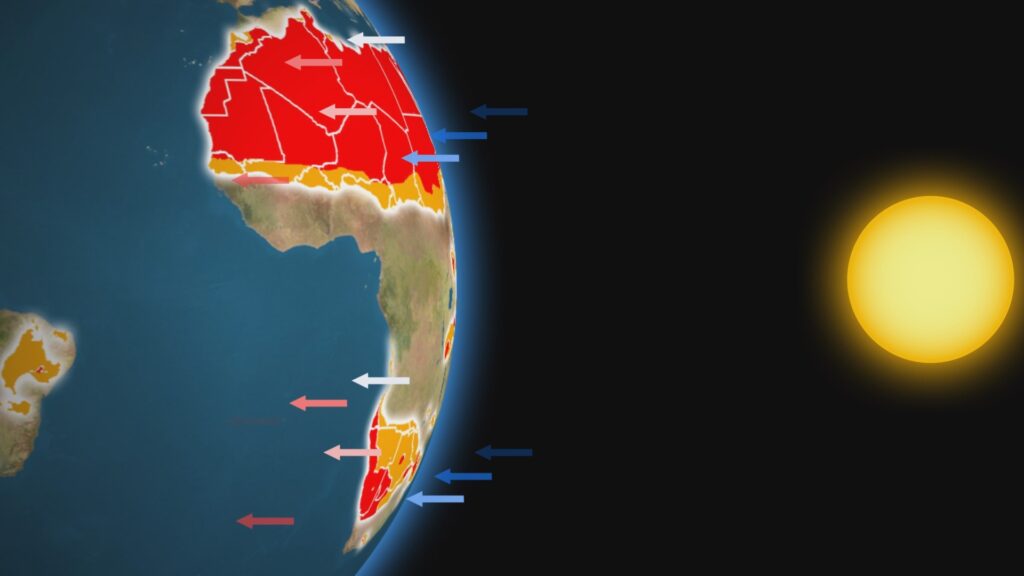

But what happens to the air after it releases its moisture? It doesn’t disappear. It moves away from the equator, toward the subtropics. Eventually, it begins to descend—typically around 30° north and south latitude. This sinking air has already lost most of its moisture and now warms as it compresses under increasing atmospheric pressure.

This descending, dry air creates regions of high pressure, where the sky remains mostly cloudless. The lack of clouds allows intense solar radiation to reach the surface, producing scorching temperatures during the day. At the same time, the dry air holds onto any remaining moisture, so rainfall becomes extremely rare.

Solar heating near the equator produces thermals that lose their moisture as rain

Tropical uplift of air must go somewhere so it moves out toward the poles

The now dry air from the tropics falls down in subtropical areas that, denied rain, lead to deserts

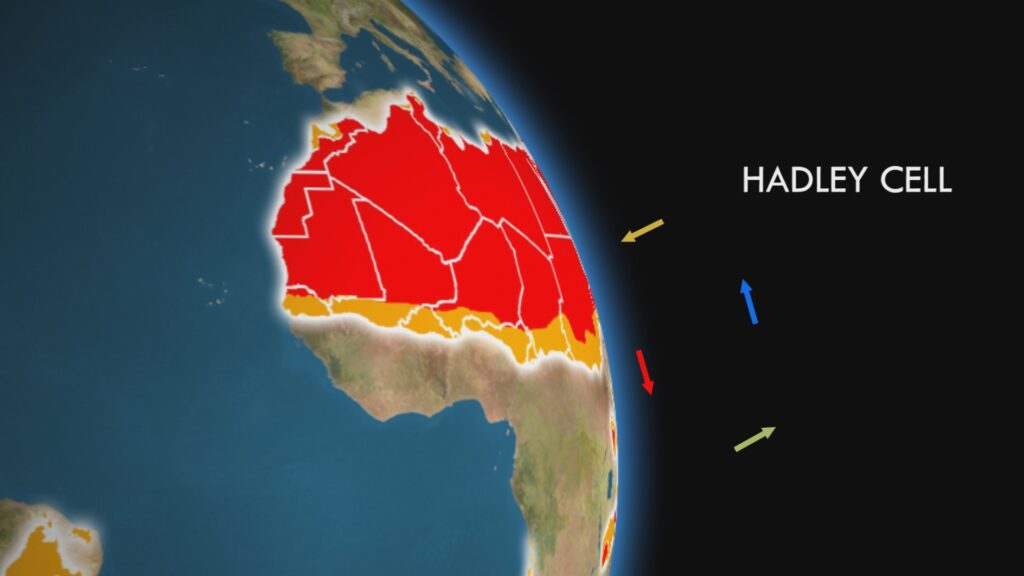

This entire cycle of rising and falling air is part of a global circulation pattern known as the Hadley Cell. The Hadley Cell explains not only the formation of hot deserts, but also the climates of tropical rainforests, savannas, and monsoon regions. It’s one of the key systems that shapes weather and climate in the tropical and subtropical parts of the world.

It’s worth noting that not all deserts form this way. Some, like the Atacama or Gobi, are classified as cold deserts and arise from entirely different processes—topics we’ll explore in later chapters.

The Hadley Cell of Tropical and Subtropical air circulation explains Tropical Rainforest, Tropical Wet & Dry and Hot Desert climates

Climate Patterns and Köppen Classifications

Hot desert climates are not all the same, but they do share some defining features. The Köppen Climate Classification System divides them into two main types, based primarily on how much rain falls annually:

-

BWh (Hot Desert): These areas receive the least rainfall, often less than 250 mm per year.

-

BSh (Hot Semi-Arid): These regions receive slightly more precipitation—enough to support scattered shrubs and grasses, but not forests.

Both climates are marked by extreme heat, particularly during the long summer months. Because rainfall is rare, the seasons in hot deserts are defined by temperature, not by wet or dry periods. Typically, there are two main seasons: a long, extremely hot summer, and a shorter, mild or cool winter.

How much temperatures fluctuate from summer to winter depends largely on two factors: latitude and distance from the ocean. The further a desert is from the equator or a large body of water, the greater the seasonal variation in temperature.

For example, Baghdad—located at 33° north latitude and far from any coastline—experiences scorching summers and chilly winters. In contrast, Mogadishu, which lies near the equator and sits on the coast of the Indian Ocean, maintains fairly stable temperatures year-round.

Another important trait of desert climates is the dramatic drop in temperature at night. With no moisture in the air and few clouds, heat escapes quickly after sunset, resulting in chilly nights—even after blisteringly hot days.

These conditions help shape not only the landscape and vegetation but also how humans adapt to life in the world’s driest environments.

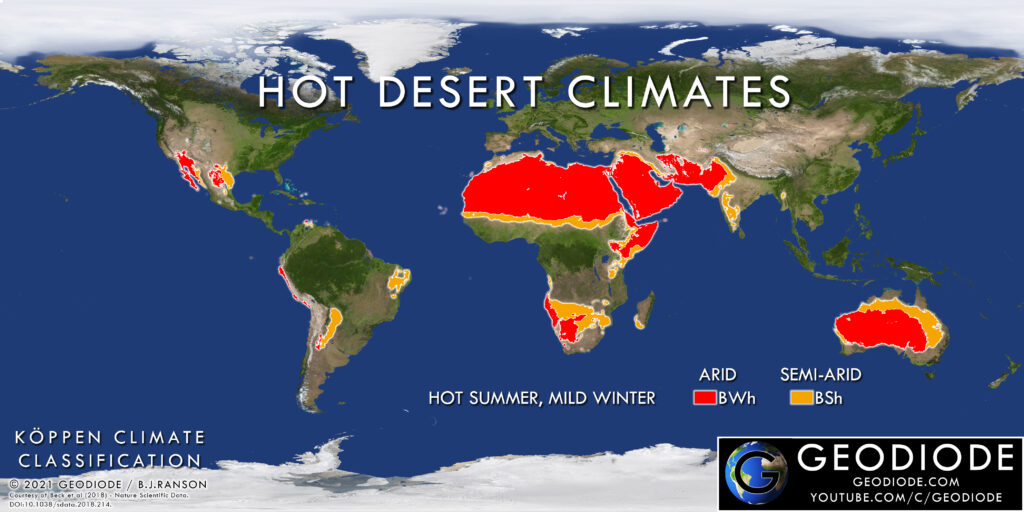

Global Distribution of Hot Desert Climate Zones

Where in the World Do We Find the Hot Desert Climate Zones?

Hot desert regions are found across multiple continents. Let’s explore their global distribution:

-

North America: The Mojave Desert in the southwestern United States spans parts of California, Nevada, and Arizona. It extends into Mexico as the Sonoran Desert, including the Baja Peninsula. The Chihuahuan Desert lies in northeastern Mexico.

-

South America: The coast of Peru is one of the driest regions on Earth, often shrouded in fog due to cold ocean currents. Inland lies the Chaco of northwestern Argentina.

-

Africa and the Middle East: The Sahara Desert dominates northern Africa and is the largest hot desert in the world. It stretches eastward into the Arabian Peninsula, parts of Iran, Pakistan, and reaches the Thar Desert in western India. In southern Africa, the Namib Desert—also foggy in coastal areas—leads into the Kalahari Desert.

-

Australia: Most of the continent is covered by arid or semi-arid land. This includes named deserts like the Great Sandy, Great Victoria, and Gibson Deserts, forming the “Red Heart” of Australia.

These deserts are shaped not only by latitude but also by ocean currents, altitude, and continental placement.

Landscapes and Biomes

The landscapes of hot deserts are defined by minimal vegetation, which exposes the Earth’s rocky surface and dry soils. These raw, open environments give us a glimpse into the geological foundations of our planet.

Because there are few plants to hold soil in place, winds often grind exposed rock into fine sand. These sands form towering dunes, which can shift and grow over time. Other areas consist of bare rock, cracked earth, or gravel plains.

Where some moisture exists, plants have adapted with incredible efficiency. Hardy shrubs are spaced out to reduce competition, and cacti dominate the scene in some deserts. These plants are uniquely designed to store water for long periods, survive intense heat, and even withstand years between rainfalls.

Sand dunes in Dubai

Cacti in Arizona

Notable Cities

Despite the harsh conditions, many major cities thrive in hot desert regions. Thanks to modern infrastructure, water management, and trade, these urban centers support millions of residents.

Climate graphs of notable cities in Hot Desert climate regions

Coursework Questions

-

How does the uplift of tropical air at the equator relate to the formation of hot deserts in subtropical regions?

-

What is the Hadley Cell and what role does it play in determining various climatic conditions in tropical and subtropical regions?

-

Explain why hot deserts, despite being at higher latitudes, can have higher temperatures than equatorial regions.

-

Why is it that some coastal areas of hot deserts feature frequent fogs?

-

What are the Köppen codes for these climates? How do they differ from each other?

-

What types of natural landscapes do we find in hot deserts?

-

Name five hot deserts and describe their location.

-

List out some countries and cities that experience hot desert climates.

Go to Chapter 5 >>